Latest News

Real Estate Transactions: April 25, 2025

Real Estate Transactions: April 25, 2025

My Turn: Blueberries and tariffs

My Turn: Blueberries and tariffs

Sheila Gilmour resigns from Greenfield City Council

Sheila Gilmour resigns from Greenfield City Council

Performances of ‘The Wizard of Oz’ at Mahar start May 2

ORANGE — Arabella Malo and Audrey Elwood played sisters in “Frozen Jr.” a year ago. Now, they’re preparing to share the same character in “The Wizard of Oz.”

As Shady Glen Diner awaits buyer, current owner extends hours, shores up staffing

TURNERS FALLS — Last June, the Shady Glen Diner at 7 Avenue A was put up for sale. Nine months later, a buyer still has not been found, but owner Charles Garbiel has extended the diner’s hours and expects to play the long game.

Most Read

Federal Street School substitute teacher alleged to have called student racial slur

Federal Street School substitute teacher alleged to have called student racial slur

PHOTOS: Greenfield celebrates Earth Day with parade, festivities

PHOTOS: Greenfield celebrates Earth Day with parade, festivities

Local protests against Trump administration continue as part of 50501 movement

Local protests against Trump administration continue as part of 50501 movement

Mother whose daughter died in Holyoke marijuana facility backs bill for worker safety

Mother whose daughter died in Holyoke marijuana facility backs bill for worker safety

Greenfield Police Logs: March 25 to April 6, 2025

Greenfield Police Logs: March 25 to April 6, 2025

HS Roundup: Mohawk Trail softball earns first win of the season following 16-4 victory over Mahar

HS Roundup: Mohawk Trail softball earns first win of the season following 16-4 victory over Mahar

Editors Picks

PHOTO: Like new again

PHOTO: Like new again

Greenfield Notebook: April 24, 2025

Greenfield Notebook: April 24, 2025

North County Notebook: April 25, 2025

North County Notebook: April 25, 2025

Two men sentenced in case of 2023 stabbing in Orange, pursuit

Two men sentenced in case of 2023 stabbing in Orange, pursuit

Sports

UMass basketball: Minutemen land UMBC guard Marcus Banks Jr.

AMHERST — Many UMass men’s basketball fans were waiting patiently for a fourth-year head coach Frank Martin to make a big splash in the transfer portal, and on Thursday afternoon, he certainly did.

Opinion

My Turn: Vote ‘no’ to lower voting age to 16 in Deerfield

On April 28, at 7 p.m., attendees at the annual Deerfield Town Meeting will be asked to vote on an article to lower the voting age to 16 years old. This same article was defeated at last year’s annual Town Meeting so why try to have a second vote?

Reenie Grybko Clancy: Confused

Reenie Grybko Clancy: Confused

Letter: Support Tim Hilchey for Selectboard

Letter: Support Tim Hilchey for Selectboard

John Walter: Why some forests should never be logged

John Walter: Why some forests should never be logged

John Babits: Democrats and gang members

John Babits: Democrats and gang members

Your Daily Puzzles

An approachable redesign to a classic. Explore our "hints."

A quick daily flip. Finally, someone cracked the code on digital jigsaw puzzles.

Chess but with chaos: Every day is a unique, wacky board.

Word search but as a strategy game. Clearing the board feels really good.

Align the letters in just the right way to spell a word. And then more words.

Business

Expanding child care options: Hilltown Children’s Center opens in Shelburne

SHELBURNE — The newly opened Hilltown Children’s Center has a mission: building a foundation of self-confidence, individualism and fun for children, while expanding the child care options available in Franklin County.

Northfield’s Wild Geese Decluttering helps clients achieve comfort through organization

Northfield’s Wild Geese Decluttering helps clients achieve comfort through organization

Cooking up an expansion: Cocina Lupita eyes second location in Turners Falls

Cooking up an expansion: Cocina Lupita eyes second location in Turners Falls

Incandescent Brewing now open in Bernardston

Incandescent Brewing now open in Bernardston

Arts & Life

Sounds Local: ‘We are all aboard a train of hope’: Oen Kennedy and Fiery Hope Chorus join forces for an inspiring performance this weekend

In 1988, at the age of 23, Eveline MacDougall founded the Fiery Hope Chorus (formerly Amandla Chorus), and she continues to serve as a director of the 35-member group.

Obituaries

Barbara Atamaniuk

Barbara Atamaniuk

Greenfield, MA - Barbara Ann Atamaniuk, 71, of Hatchery Road, a lifelong resident of Franklin County, died peacefully early Tuesday morning, April 22, 2025 at Charlene Manor in Greenfield with her family at her side following a lengthy ... remainder of obit for Barbara Atamaniuk

Joyce A. Makowski

Joyce A. Makowski

Joyce A. (Sliwa) Makowski SOUTH DEERFIELD, MA - Joyce A. (Sliwa) Makowski, 91, of Conway Road passed away peacefully on Monday Morning at Cooley Dickinson Hospital after a brief illness. Joyce was born in Northfield, a daughter to Joseph... remainder of obit for Joyce A. Makowski

David Martin

David Martin

North Fort Myers, FL - David Russell Martin, born 5/9/1938 to Leslie and Ruth( Mayer) Martin in Greenfield, MA. Passed away on April 11, 2025. David was brought up in Northfield, MA, where he always said he had one of the best child... remainder of obit for David Martin

Edward Racz Jr.

Edward Racz Jr.

Edward Racz, Jr. Bethlehem, PA - Edward Racz, Jr., a cherished husband, father, grandfather, and friend, passed away on April 16, 2025, in Bethlehem, PA, with his loving wife by his side. Born on October 23, 1948, in Germany, he was the ... remainder of obit for Edward Racz Jr.

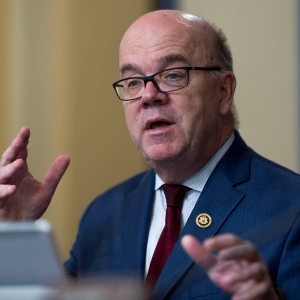

U.S. Rep. Jim McGovern announces death of daughter, Molly, who battled cancer

U.S. Rep. Jim McGovern announces death of daughter, Molly, who battled cancer

The Academy at Charlemont among 148 teams, sole Massachusetts school, in national quiz bowl finals

The Academy at Charlemont among 148 teams, sole Massachusetts school, in national quiz bowl finals

Despite frustration over process, Leverett Selectboard OKs 14% school funding increase

Despite frustration over process, Leverett Selectboard OKs 14% school funding increase

Small CPA projects, outstanding bills coming to Whately Special Town Meeting

Small CPA projects, outstanding bills coming to Whately Special Town Meeting

Patients seek new primary care doctors after North Quabbin Family Physicians closes

Patients seek new primary care doctors after North Quabbin Family Physicians closes

McGovern reflects on visit with two students in detention facilities in Louisiana

McGovern reflects on visit with two students in detention facilities in Louisiana

‘We knew he was going to be special’: Deerfield Academy alum Elic Ayomanor set to hear his name called during 2025 NFL Draft

‘We knew he was going to be special’: Deerfield Academy alum Elic Ayomanor set to hear his name called during 2025 NFL Draft HS Roundup: Brayleigh Burgh powers Franklin Tech softball past Mahar, 18-0 (PHOTOS)

HS Roundup: Brayleigh Burgh powers Franklin Tech softball past Mahar, 18-0 (PHOTOS) HS Roundup: Smith Vocational baseball pulls ahead late to defeat Franklin Tech, 6-3

HS Roundup: Smith Vocational baseball pulls ahead late to defeat Franklin Tech, 6-3 HS Roundup: Mohawk Trail softball earns first win of the season following 16-4 victory over Mahar

HS Roundup: Mohawk Trail softball earns first win of the season following 16-4 victory over Mahar Creating a ‘mecca of local art’: JJ White opening Art Deviation Gallery & Store in Greenfield

Creating a ‘mecca of local art’: JJ White opening Art Deviation Gallery & Store in Greenfield Speaking of Nature: Fascinated by ferns: Ferns figured out how to say goodbye to the aquatic environment hundreds of millions of years ago

Speaking of Nature: Fascinated by ferns: Ferns figured out how to say goodbye to the aquatic environment hundreds of millions of years ago Fascinated by the seemingly infinite uses of eggs: Creamed eggs are an easy and delicious post-Easter nursery food

Fascinated by the seemingly infinite uses of eggs: Creamed eggs are an easy and delicious post-Easter nursery food From corsets to Spanx: Historic Deerfield opens the season with ‘Body by Design: Fashionable Silhouettes from the Ideal to the Real,’ May 3

From corsets to Spanx: Historic Deerfield opens the season with ‘Body by Design: Fashionable Silhouettes from the Ideal to the Real,’ May 3 Bach and better than ever: UMass Amherst biennial Bach Fest returns April 25-27 with a multitude of concerts and symposia

Bach and better than ever: UMass Amherst biennial Bach Fest returns April 25-27 with a multitude of concerts and symposia