Faith Matters: It gets better, and harder: Discovering a growing need to see your commitment all the way through

| Published: 05-03-2024 12:14 PM |

There is and there always has been within the Christian tradition a lively debate about the divinity of the person Jesus. We encounter it in our own pews at the holiest times of the year, in our unease, at Christmas, with the virgin birth, and in our doubting, at Easter, in the resurrection. I keep surprising myself — an unchurched, “questioning believer” — with how easily I embrace these magical and mysterious parts of the story. But I am uninterested in the debate.

In an age of general religious decline and especially church decline (at least in our part of the world), the particulars of such debates are not only unimportant, they are often unhelpful. People aren’t looking for debates rooted in lost language and forgotten doctrines. They are searching for meaning and purpose; for an organizing principle, a way to understand the strangeness and absurdity of this existence we have and must endure. Surrounded by unfairness and hardship — by poverty wages and forever wars — we recognize that we need a way to defend human life itself; a way to regain trust in the worthiness and the dignity of humankind.

And most of all, we want to participate fully and equally in that kind of conversation. We want to bring our whole selves to bear on it, and experience growth and change alongside the shining faces of others, which are suddenly lit up by the opportunity to encounter us and for us to encounter them. At least here in New England, we still want what Emerson wanted: “an original relation to the universe,” and “a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition,” and “a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of [others].” We long for sacred space and sacred time that we ourselves get to make, to re-member each other in what Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. described as a “luminous and genuine” siblinghood.

When I went searching for my own sense of purpose — when I started to encounter others as they truly are and experienced being seen as I truly am — I was in rural Eastern Ontario, and virtually the only houses of worship belonged to mainline, Protestant denominations. I stepped tentatively into the great stream of Christian thought and practice really by default. It was only later in seminary, in the pursuit of ordination, and certainly now in the practice and fellowship of ministry in Ashfield that I have become a Christian by belief. I share this not because my journey is particularly important, but because I wonder if it is more common than the Church realizes.

In Ashfield, the only requirements for participating in our church community are a willingness to be recognized as a sacred and precious person, and a covenantal commitment to recognize the sacredness and preciousness of everyone else. We must genuinely believe we live among souls (even if this is not the language each of us would use).

But of course there is a catch. If you intend to uphold this willingness and this commitment — if you take this spiritual or religious stance sincerely, “with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind” (Luke 10:27) — you will discover a growing need to see your commitment all the way through. You will find yourself caring for others who are in distress and in grief; you will be exposed to struggles that are not and had never been your own but now become yours through your deepening sense of unity with others. You will find yourself every bit as responsible for the well-being of your neighbors and complete strangers as you are for your own family.

And it gets better, and harder. Things that are endemic to life in this country will become scandalous to you, things like unemployment and incarceration, worsening poverty and the disappearing middle class. A lifetime of struggle will sprawl out before you, as you experience a true revolution of values, like King described, causing us to see that “true compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar,” that rather, “[compassion] comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.” Finally, as King did, we will “look uneasily on the glaring contrast of poverty and wealth … and say ‘This is not just.’”

Because once we have re-membered each other in our sacred spaces, and into luminous siblinghood, we will know that there is no justification for throwing away any life, since every one is sacred and precious; and that leaving one person behind, for any reason, undermines the sacredness and preciousness of us all. People debate if Jesus was divine. What matters to seekers today is that the love that totally consumed him may yet make us divine.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Lesbian bar opens in Greenfield: Last Ditch is the new space for the Valley’s queer community

Lesbian bar opens in Greenfield: Last Ditch is the new space for the Valley’s queer community

Warwick residents, Selectboard, frustrated by internet connection delays

Warwick residents, Selectboard, frustrated by internet connection delays

Petition seeks removal of Tucker Jenkins from Shelburne Police

Petition seeks removal of Tucker Jenkins from Shelburne Police

Turners Falls man pleads guilty to child porn charges

Turners Falls man pleads guilty to child porn charges

Driver taken by helicopter following Warwick crash

Driver taken by helicopter following Warwick crash

PHOTOS: ‘Overpass Day’ held to protest Trump administration

PHOTOS: ‘Overpass Day’ held to protest Trump administration

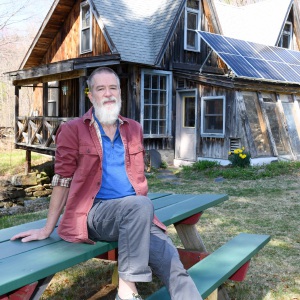

Reverend Jones is the minister of the First Congregational Church in Ashfield and chair of the Church and Ministry Committee in the Franklin Association of the United Church of Christ.

The First Congregational Church in Ashfield is an Open and Affirming congregation, uniting believers, questioners, and questioning believers in a range of community and justice-oriented ministries. The church hosts both the Hilltown Churches Food Pantry in its downstairs Friendship Hall and, during winter months, Ashfield’s Share the Warmth community program in its upstairs Green Room. Join us on Sundays at 10 a.m., both in-person and on Zoom, for worship and fellowship. We can be reached by phone at 413-628-4470, and online at www.ashfielducc.org.

Living and breathing democracy: Smithsonian museum sets up traveling exhibit inside the Mohawk Trail Regional School library

Living and breathing democracy: Smithsonian museum sets up traveling exhibit inside the Mohawk Trail Regional School library The bomb that never dropped: New book details how Massachusetts planned during the Cold War

The bomb that never dropped: New book details how Massachusetts planned during the Cold War Her time in the spotlight: Amherst artist turns 90 and has first-ever public exhibit

Her time in the spotlight: Amherst artist turns 90 and has first-ever public exhibit