Faith Matters: We are all in the same boat: Finding God and our common humanity in ‘the between’

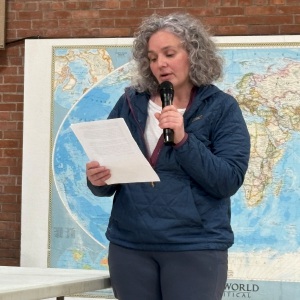

Ben Tousley on the Greenfield Common. Staff Photo/Paul Franz

| Published: 05-17-2024 12:30 PM |

Years ago, I stood with some family members and a large crowd of strangers on a whale watch boat anxiously anticipating the appearance of the first whale. When the mighty leviathan breached the water quite close to one side of our boat, all let out a collective gasp. The whale, which seemed nearly the size of our boat, made an arc and disappeared into the water — leaving us in awe-filled silence for several seconds — only to reappear now on the other side of our vessel, spouting its geyser, dancing alongside us and eliciting another collective gasp.

We know such moments of truth and beauty when some presence like a newborn child or a great singer or an adorable puppy comes among us. In those shared moments we are not defined by race or gender or political preference. We feel we are all in the same boat. We come together in our common humanity with hearts and spirits open to such presence and often, to one another.

In these times when our world and our country experiences such great division into warring groups, I find it helpful to think of God as creative spirit which abides among and between us. In the words of St. Paul: “He is our peace who has made us both one, and has broken down the dividing wall of hostility … that he might create in himself one new person in place of the two, so making peace, and might reconcile us both to God.” (Ephesians 2: 14-16)

The vision of God’s truth, beauty, love and peace emerging between two different people is echoed by the Jewish mystic and philosopher, Martin Buber. Buber and his fellow Hasidim believed that true relationship is possible when people are willing to encounter one another in a spirit of mutuality, to engage in open dialogue with the possibility not of giving up their differences but of finding common ground on which both might stand. In fact, Buber writes, by entering the sphere of the between — a sphere which reaches out beyond the special sphere of each: “Our own relation to truth is heightened by the other’s different relation to the same truth.” Thus, through such fearless dialogue, we open ourselves to changing, to becoming the “new person” St. Paul names.

When I was in my early 30s, I was co-instructor for an Outward Bound-modeled expedition into the mountains of West Virginia with a group of Black teenage boys who were one misstep away from being sent to reform school. The boys were from impoverished families, most had never been camping and some had never been out of the city. As a middle class white person, it seemed I had little in common with them. They were fighters. I tried to practice nonviolence which for them seemed absurd.

But in the course of hiking, caving and rock climbing for nearly three weeks, we came to know one another not as stereotypes but as distinct individuals. Our trust developed to the point of holding the rope for one another as we scaled steep cliffs and as we helped each other through the scary darkness of underground caves. We were in the same boat and we were learning cooperation.

Martin Luther King Jr. consistently held up his vision of our interconnectedness, reminding white ministers in his “Letter From a Birmingham Jail”: “In a real sense, all life is interrelated, tied in a single garment of destiny.” Locked in the bitter struggle against white segregationists, King never gave up in seeking to uphold our common humanity through peaceful dialogue.

Dr. King was greatly influenced by the nonviolent leadership of Mahatma Gandhi in the Indian struggle for freedom from the British empire. Gandhi called his method of nonviolence Satyagraha which means “truth force.” He believed that nonviolent action in the midst of an unjust situation required the aggrieved party to witness to the truth in a way that maximizes mutuality and refuses to do harm.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Lesbian bar opens in Greenfield: Last Ditch is the new space for the Valley’s queer community

Lesbian bar opens in Greenfield: Last Ditch is the new space for the Valley’s queer community

PHOTOS: ‘Overpass Day’ held to protest Trump administration

PHOTOS: ‘Overpass Day’ held to protest Trump administration

Gov. taps two from western Mass. for Superior Court bench

Gov. taps two from western Mass. for Superior Court bench

Turners Falls man pleads guilty to child porn charges

Turners Falls man pleads guilty to child porn charges

New provision allowing beer sales at farmers markets sees mixed reactions

New provision allowing beer sales at farmers markets sees mixed reactions

Petition seeks removal of Tucker Jenkins from Shelburne Police

Petition seeks removal of Tucker Jenkins from Shelburne Police

Prior to civil disobedience, Gandhi insisted on a disciplined investigation of facts from which truth might emerge. Second, a sincere attempt at arbitration and finding common ground must be undertaken. Third, the oppressed party must engage in a searching process of self-examination to determine errors in judgment or perception. Most important, as Buber taught, we must enter into relationship with our adversary with an open mind and spirit, willing to change our mind having found a flaw in our position. Gandhi believed that only an outcome which transforms both partners in a conflict could be considered truth in action.

As nations, factions and individuals, we often find ourselves stuck in opposing positions — pro this and therefore anti-that. Yet that ancient vision of our common humanity which Buber, King and Gandhi sought to follow offers a way to find our place back to the same boat. In the midst of our self-righteous disputes, God is that creative spirit which calls us to mutual dialogue with love and respect. May it be so.

Ben Tousley recently retired from his work as hospice chaplain after 20 years working in the Pioneer Valley and on the North Shore of Boston. A graduate of Harvard Divinity School, Ben also served as adjunct professor at Springfield College for 23 years. As a folksinger and songwriter, Ben has recorded seven albums of original songs. He lives in Greenfield.

Living and breathing democracy: Smithsonian museum sets up traveling exhibit inside the Mohawk Trail Regional School library

Living and breathing democracy: Smithsonian museum sets up traveling exhibit inside the Mohawk Trail Regional School library The bomb that never dropped: New book details how Massachusetts planned during the Cold War

The bomb that never dropped: New book details how Massachusetts planned during the Cold War Her time in the spotlight: Amherst artist turns 90 and has first-ever public exhibit

Her time in the spotlight: Amherst artist turns 90 and has first-ever public exhibit