Play it again, Sam: Shea Theater to show ‘Lovejoy’s Nuclear War’ to mark 50th anniversary of Montague tower toppling

|

Published: 02-09-2024 12:12 PM

Modified: 02-09-2024 3:07 PM |

In the fall of 1973, Wendell resident Dan Keller drove to Bradley International Airport in Connecticut to pick up friend Sam Lovejoy and mentioned to his pal that he wouldn’t believe what had been built back home on the Montague Plains.

The two drove north on Route 47 and Lovejoy saw with his own eyes the 500-foot weather tower Northeast Utilities had erected to test wind direction. The data was to be used to determine, in the event of an accident, which way the radiation would blow from the nuclear power plant the company wanted to construct.

“He said, ‘Someone’s gonna knock it down,’ and I thought for … a few seconds and I realized who it was that was going to do it,” Keller said with a laugh late last month.

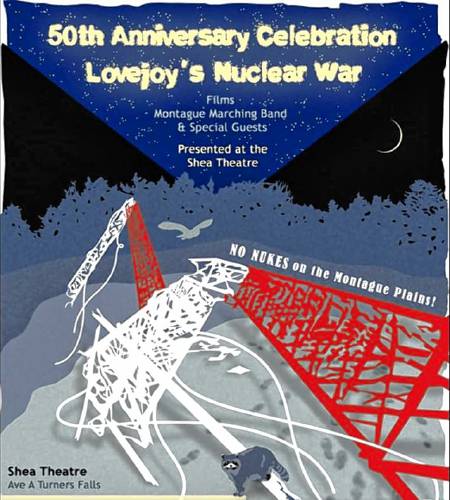

Months later, in the middle of the night on Feb. 22, 1974, Lovejoy used a crowbar to loosen three of the tower’s turnbuckles and topple the structure, more or less birthing the anti-nuke movement. This act of civil disobedience, and the ensuing trial, was chronicled in Keller’s documentary film, “Lovejoy’s Nuclear War,” which was released the following year and is slated to be shown at the Shea Theater Arts Center on the event’s 50th anniversary as a way to commemorate Montague’s aborted atomic age.

“We’re hoping that it’s not a political issue-fest,” Lovejoy said over coffee at The Lady Killigrew Cafe in Montague. “We’re hoping that it’s more like, you know, a celebration of the fact that you can live in the valley safely without driving up [Interstate] 91 and saying, ‘Holy [expletive], what is that?’”

A group called the Montague Marching Band will lead off by playing some music. A screening of “Lovejoy’s Nuclear War” will follow, as will the short-form documentary, “The Tower” by Scott Hancock. There will also be a Q&A session. Poet Paul Richmond, of Wendell, will serve as master of ceremonies. Doors open at 6 p.m. and the event begins at 7 p.m. Tickets are $16 in advance and $20 at the door. They can be reserved in advance at sheatheater.org or, pending availability, purchased at the door the evening of the event. Proceeds will benefit organizations that fight against nuclear energy.

Linda Tardif, the Shea’s managing director, said the theater agreed to host the event because it is an inclusive space that encourages dialogue from different viewpoints.

“We are a place for those who’ve been here and for those who are just arriving, and we are thrilled to host the celebration ... that honors the very brave move made by one of our very own community members 50 years ago,” she said.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Report: Montague Police internal affairs investigation ‘biased’

Report: Montague Police internal affairs investigation ‘biased’

Laid-off Kennametal employees ponder what’s next

Laid-off Kennametal employees ponder what’s next

Greenfield native Sam Calagione, founder of Dogfish Head Brewery, to throw out first pitch at Fenway Park on Friday

Greenfield native Sam Calagione, founder of Dogfish Head Brewery, to throw out first pitch at Fenway Park on Friday

My Turn: Call us Cinderella Town

My Turn: Call us Cinderella Town

Springfield man held without bail in case of September foot pursuit in Greenfield

Springfield man held without bail in case of September foot pursuit in Greenfield

Real Estate Transactions: April 18, 2025

Real Estate Transactions: April 18, 2025

“Lovejoy’s Nuclear War” runs an hour and includes interviews with Lovejoy, other locals, two people from Northeast Utilities and Dr. Howard Zinn, a Boston University political science professor who testified on Lovejoy’s behalf. The film went worldwide, getting translated into roughly 30 languages, and galvanized Keller’s film and video production and distribution company, Green Mountain Post Films. It also consists of footage of the wreckage, filmed by Keller within a day or two of the toppling because he knew the utility company would build a new tower in no time, which it did.

“It’s just very dramatic, to see all that twisted metal. It’s a huge amount of metal,” Keller said. “It’s quite a disaster, really.”

“I felt terrible,” Lovejoy sarcastically chimed in with a cackle.

In the mid-1970s, Keller’s main job was filming Dartmouth College football games, “so I always had the camera ready, and plenty of film.” He filmed the matchups with two cameras — one color, and one black and white. The color film was for alumni posterity and the black-and-white one was for game study and strategy. This is why “Lovejoy’s Nuclear War” has frames in both black and white and color.

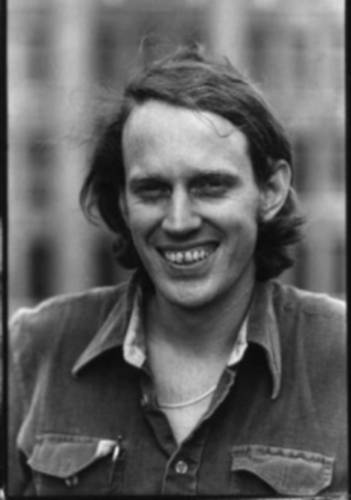

Lovejoy, who now lives in Montague Center, was acquitted on a technicality following a nine-day trial in Franklin County Superior Court in September 1974. He had faced five years behind bars for destruction of personal property. The power plant project, which would have included at least two 600-foot cooling towers, was delayed four years for review before Northeast Utilities pulled the plug. Lovejoy said he wouldn’t hesitate to do it again, though he feels it would not be necessary today, as there is such widespread opposition to nuclear power.

He and Keller have heard from many people who said they would not have moved to the Pioneer Valley if there was a nuclear power plant here. And Lovejoy and Keller, former Amherst College peers, said they would have left the area decades ago if it had been built.

But Keller’s well-kept secret for years? He drove Lovejoy to the area near the tower site that night and was the only other person to see the tower come down, though he was not at the scene.

“After I dropped him off I went over to Millers Falls and drove up on a little hill over there, where I could see the tower. And I waited. I could see it from Millers … all of a sudden it started to move a little bit,” he recounted while standing next to Lovejoy last month roughly 100 yards from the site. “At first it started to tremble a little bit, started to just vibrate a little bit. And then it started falling. And the way it fell was, it sort of fell into three or four sections. So it was, like, disjointed in mid-air, but the lights stayed on for some reason for a while as this was all collapsing. So it didn’t tip over as one big unit – it kind of collapsed, like a big skeleton.”

Keller said he then drove home to Wendell and went to bed.

As for Lovejoy, he watched the triangulated tower fall to the ground and then, carrying a four-page statement in which he took responsibility for his actions, set off to Montague Police Department, which at that time was in the Montague Town Hall basement. Lovejoy followed some power lines to Turners Falls Road, where he encountered a couple of Montague Police officers in a cruiser. He introduced himself and got a ride to the police station. He handed the statement to Sgt. Donald Cade, who read it and then, according to Lovejoy, said, “Well, I guess I’m going to arrest you.”

Lovejoy explained he picked Feb. 22 for a very specific reason – it is the birthday of President George Washington, who according to legend chopped down a cherry tree as a child and confessed to the act.

“I cannot tell a lie,” Lovejoy said, quoting the supposed words of the first commander in chief.

Lovejoy’s sudden celebrity jump-started a public speaking career that culminated with “No Nukes: The Muse Concerts For a Non-Nuclear Future,” a five-night concert at Madison Square Garden in 1979 featuring acts such as Bonnie Raitt, Graham Nash, Carly Simon and James Taylor. The concert — organized by Musicians United for Safe Energy, or MUSE, an activist group founded by Raitt, Nash, Jackson Browne, Harvey Wasserman and John Hall — became a movie and an album, and raised a lot of money for the anti-nuke movement.

Sounds Local: Cover bands abound at the Shea: Big Yellow Taxi will perform much of Joni Mitchell’s ‘Ladies of the Canyon’ this Saturday

Sounds Local: Cover bands abound at the Shea: Big Yellow Taxi will perform much of Joni Mitchell’s ‘Ladies of the Canyon’ this Saturday Speaking of Nature: A surprise in my maple tree: Porcupines just want to find something tasty to eat and be left alone

Speaking of Nature: A surprise in my maple tree: Porcupines just want to find something tasty to eat and be left alone Little pillows of golden goodness: The beignet recipe of your dreams, courtesy of our beloved local Wells Provisions

Little pillows of golden goodness: The beignet recipe of your dreams, courtesy of our beloved local Wells Provisions The cost of addiction: New novel draws on Valley backdrop to explore how substance use upends people’s lives

The cost of addiction: New novel draws on Valley backdrop to explore how substance use upends people’s lives